August/September 2018

EFTA Blog—August 2018

75TH ANNIVERSARY

It is a land is populated with ghosts… at least to me, it is.

Naftali. Chanah. Shamei. Toncia.

Names of four of my murdered family, four out of more than 80.

Lives eradicated, and now in memory, resurrected.

I’ve just returned from Poland. It was 75 years ago, on August 1, 2, 3, 1943, when Jews from the Kamionka/Strodula Ghetto— Jews from Bedzin, Sosnowiec, and the Zaglembia region of western Poland—were deported to Auschwitz.

Entrance Gate at Auschwitz–Arbeit Macht Frei / Work Makes You Free

In truth, I had no need to see Poland again; I had been there multiple times to copy, research and work on photographs from the liquidation of Bedzin Ghetto—but this time was different.

Ann Weiss in 1988, copying photos at Auschwitz

This time was the 75th anniversary of deportation of Jews from Zaglembie, many of whose photos appear in my book, film and traveling exhibition—and 200 of their descendants would be coming. It was because of these descendants—so we could talk, and together honor the memory of dead families—that I felt compelled to return to this land of ghosts and blood.

I was asked to give a presentation by the Zaglembie World Organization. In a crowded room in Krakow, I described finding unknown personal photos in a locked room at Auschwitz. And although millions of personal photos were carried into slave labor and death camps throughout the Third Reich, only the photos from this one large transport still existed! Others had been deliberately destroyed by the Nazis, as this one was supposed to have been—I learned from Professor James Young (who learned it from artist Yehuda Bacom, who heard it directly from the Sondercommando, when Bacom was a prisoner at Auschwitz Birkenau) that there was even a special crematorium in Auschwitz just to burn these personal photos!

Miraculously, however, in August 1943, David Schmulevitz, a leader of the Jewish Underground, ordered the teenage girls working in ‘Canada’ (the sorting warehouses of confiscated items) to save (and hide) photos from this large transport from Zaglembie. He understood that by late summer 1943, much of Polish Jewry had already been destroyed. As an Underground member told me, “David Schmulevitz said, “If we can’t save the people, let us at least try to save their memories!”

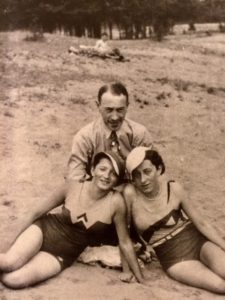

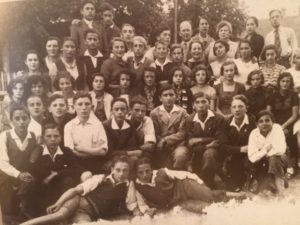

Vacation photos. Wedding portraits. School Outings. Formal and informal photographs of life, depicting precious moments shared with precious people.

This photo of a mother and daughter was brought to Auschwitz-Birkenau in August 1943

Wedding portrait of Artur and Grete Huppert, brought to Auschwitz August 1943

I’ve been researching these personal photos for over 30 years. Many faces now have names. Many names now have stories. Now, on the 75th anniversary of the destruction of the ghetto, I returned to this holy/unholy blood soaked ground— to share, to memorialize and to listen.

More took place than I could possibly have anticipated. More. Even more.

A few highlights:

FRANIA RUSINEK—AND RELATIVES FROM AUSTRALIA AND ISRAEL

I was able to show Rina Kahan, the trip’s organizer, as well as David Ruschinek from Israel and his father Benjamin from Australia, a group of unknown photos of their beautiful relative, Frania Ruskinek. Their shock, and reverence, at seeing the face of their beautiful Frania can scarcely be described. At this writing, I have sent copies of Frania’s photo to her family members, scattered around the globe, and they are in their hands right now.

Frania Rusinek (bottom left) of Bedzin, Poland

Ben (father) from Australia and David (son) from Israel, both relatives of Frania Rusinek

Other families in other countries received other photos. In turn, they have sent me remarkable accounts, of the families they lost, of the survivors that remained, and of the impact of seeing these photos that they never knew existed. These will be shared, after I receive their permission, at another time.

We were honored to have with us, among the 200+ descendants, several surivors: Miriam and Fred Ferber of Detroit (Miriam was a baby in Sosnowiec when her mother saved her life by entrusting her, at 7-months, to a Polish family), Dasha Rittenberg, now of NYC, then of Bedzin, and Esther Peterseil, who with her daughter, gave an unforgettable presentation on our first Friday afternoon (just following my talk). Excerpts of Esther’s words, once I ask permission, will be shared at another time. For now, just look at the face of a woman who, not only survived, but who triumphed over the Nazis by the way she has lived and by the family she has raised.

Ester Petersil with two of her grandsons

AUSCHWITZ BIRKENAU

In sharp contrast to my first trip in October 1986, when the day was obscenely beautiful, and sky was the bluest of blues, on this 2018 trip, the sky was black with clouds and the rain pummeled us. This felt more right.

Crowded together under Birkenau’s iconic entrance, even with umbrellas, in minutes we were completely soaked. Wet and uncomfortable, it was hard not to think of other times when slave prisoners were cold, wet, starved, and had no relief at all. To us, it felt absolutely right that, soaking wet, today we were trudging though muddy Auschwitz II (also known as Birkenau), on the same terrain where the Zaglembie Jews walked 75 years ago.

Through the pelting rain, we ran to one of the few wooden barracks still standing. Most had been burned by the retreating Nazis, with only brick chimneys remaining, as silent sentinels to mark the spot where so many had once suffered, and died.

My own closest relatives did not die here. Instead they were forced to march many miles in the oppressive July 1943 heat, on Tisha B’Av, where they were pushed into pits and shot. There they still remain in a mass grave at Janowska, which was then in Poland, and is now in Ukraine. This summer is the 75th anniversary of their murders as well.

Although I am not related by blood to the Zaglembe Jews, whom we are honoring here, many years ago, several survivors ‘admitted’ me into the ‘Zaglembie Club’ with a simple explanation: “You’ve been with us so long with your pictures, now you’re one of us!” And that’s truly the way I feel.

At Auschwitz I, where political prisoners were kept, we walked through brick buildings and tree-lined paths. As more than one participant commented: “This looked like a nice little brick village, not like the horror I expected!” However, once you enter the ‘Jewish Building’ with its evidence of death still remaining—mounds of hair, bent spectacles, gold wedding rings, thousands of broken shoes, prosthetic limbs—the image of the ‘nice little village’ immediately disappears.

Auschwitz looks both the same, and also quite different, from the way I remember. The hair clumps, matted together, seemed much smaller now. I asked the guide, “Where are those long braids tied with satin ribbons?” They had broken my heart many years ago, when I first saw them, and now I could not find them at all. The guide simply replied, “Auschwitz is not preserving the hair.”

Does that mean that the hair disintegrates and gets thrown away? The tour continues and there is no time to ask this kind of question. I had already lost my group again, and another ‘handler’ had come back to find me.

Even the piles of shoes looked different to me now. When I was lost here 32 years ago, Auschwitz was closed, except for the people in our small group. Then I was alone in that massive gallery of shoes. Now I was in a massive crowd of high school students, having lost my group again. [Note to future organzers: I was not then, nor am I now, very good at staying with my group!].

The shoes, then and the shoes now, were overwhelming in number. 30,000 pair of shoes. Today I noticed a little display of shoes at the start of the gallery that I had not seen before, featuring the more unusual and more colorful shoes; and at the very front were the most heartbreaking of all: the shoes that once belonged to small children.

These shoes are several hundred of the 60,000 (30,000 pair) shoes left, from the last few days of Auschwitz-Birkenau, January 1945, when the Nazis operated the gas chambers, non-stop, to kill as many Jews as possible, before evacuating the camp, when the Soviet army was approaching.

DEPUTY DIRECTOR AND HENRI LUSTIGER-THALER

Deputy Director Andrzej Kacorzyk of State Museum of Auschwitz-Birkenau was the capable point person for our visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

He believed that a visit to Auschwitz, where so much terror had already taken place, should now lead to more reflection, and should make visitors try to create a better world. I agree, with all my heart.

Deputy Director of Auschwitz, Andrzej Kacorzyk, with Ann Weiss and Professor Henri Lustiger-Thaler (holding papers) after tour of Auschwitz I and before tour and ceremony at Birkenau/Auschwitz.

Professor Henri Lustiger-Thaler gave several lectures. Among other projects, he is looking at remnants of pre-war Jewish life (with Karolina and Piortr Jakowenko) in a book and exhibit called Ghost LandsL Zaglembie and Upper Silesia; and he is also examining the experiences of Orthodox Jews during the Shoah, a less researched topic in the canon of Holocaust Studies. In addition, with a cadre of talented colleagues, Henri is organizing a special exhibition, to be located at the entrance gate of Auschwitz I, in order to heighten visitors’ empathy and humanity, as they enter.

Note: Henri is a relative of the famous French Cardinal Aaron Jean-Marie Lustiger (1926-2007) who, as a Jewish child pretending to be Catholic, was hidden during WWII. Although never renouncing his Judaism, Aaron converted to Catholocism after the war, at age 14, taking the name ‘Jean-Marie’. He rose to the highest ranks of the Catholic Church in France, and there was even speculation that Cardinal Lustiger might become the world’s first “Jewish Pope”! Alas, he did not.

FRED FROM GERMANY

While trudging through blinding rain in Birkenau, a tall giant of a man, Fred Frenkel from Munich, Germany, walked beside me and said these unforgettable words: “ Twelve years ago, a miracle happened in my life—because of your book!” He explained, “Not only did I find my relative in your picture of Furstenberg Gymnasium (Note: Furstenberg was an elite high school in Bedzin), “but through this picture, I even discovered that my long time friend in Germany was also my relative! Your book started all this!”

Here is Fred’s relative, Jonas Testyler, the start of Fred’s ‘miracle’!

Fred Frenkel and Ann in Birkenau, in front of the bucolic grove where Hungarian Jews waited to be gassed

Under rainbow umbrella, Ann and Miriam Scharf of Los Angeles, near railroad tracks at Birkenau .As you can see from Miriam’s blue wet shirt, our umbrella was effective in only a limited way.

How thrilled I am to learn that another connection was made through the book, The Last Album: Eyes from the Ashes of Auschwitz-Birkenau. With letters arriving to me almost every day from people I met on the trip, it seems that we have many new connections being made.

MEETING RELATIVES OF NUNBERG AND SCHWARTZBERG FAMILIES

Many years ago, I interviewed Shaja Nunberg, who explained that his father’s family (the Nunberg’s) housed the Bes Yaakov School for religious girls in Bedzin on the 2nd floor of their family home, and that the Schwartzberg Family (his mother’s family) housed the Rosh Yeshiva (Head of the Yeshiva). Now in Poland, I met a large contingent of Nunberg’s and Schwartzberg’s—some siblings, some cousins— from DC/Virginia; NYC; Oregon; Saranac Lake; New Jersey, etc.)—Although the people (including Sam Weiss z”l of Falls Church, VA) who shared their family stories with me are long since dead, it has been incredible to now be with the children, grandchildren and other descendants of this generous Bedzin family.

Noah and Rebecca Nunberg with Josh Schwartzberg and two of his three sons. Here we are at an extraordinary restaurant located in the Old Market Square (Starry Rynek); It was in this building, built in 1364, that we shared an unforgettable meal, in an unforgettable setting, with lively conversation, and a beautiuful surprise at the end: a Beethoven Sonata played on the grand piano in the ‘Pompei Room’ by an 18 year old waiter!

Harry Birnholz, a member of the Nunberg Family, with Ann in one of the few remaining barracks in Birkenau.

Closeup of a row of latrines in the Birkenau barrack

Another Numberg relative is Harry Birnholz, with whom I explored latrines at Birkenau (I admit we make it look like more fun than is reasonable). It seems that ‘gallows humor’ —where one can laugh even in the most un-funny of circumstances—was at play here. Being in Auschwitz where so many suffered and died is certainly not funny, but being here together, with this group of descendants, not only made it extremely meaningful, but at certain moments—like this one where we had a choice: to cry or laugh. At this moment, we chose to laugh. At others, the only choice possible was tears.

There is a sauna building at far edge of Birkenau that I had never seen before. Despite my many trips to Auschwitz, I had never walked to this part of the complex, I didn’t even know where it was—and yet, it was an important destination for me. Over many years, people had mailed me photos of it to me, and shared stories about it. Why did they do this and why was this place so important to me? Both are reasonable questions. The answer is simple: Inside the sauna, on large panels, are mounted hundreds of photos—and these photos are the very same ones I’ve talking about, researching and looking at for over three decades! These are the photos from Zaglembia!

I was scheduled to give a talk in front of that sauna wall of pictures but the weather on this day was so horrible that the Auschwitz personnel made it clear: there was no time to do both. If we were going to have the memorial ceremony at the site of the former gas chamber, there was no time to visit the sauna wall.

Of course we chose the ceremony—heart wrenching words, prayers, and feelings. After the powerful ceremony was finished, each person lit a yarzeit candle and wrote the names of their dead families on small white flag-like cards, which were then pushed into the resistant ground. I wrote the names of my murdered family on one. On the second, I wrote nothing—and in its blankness, to me, the absence of names symbolized those millions whose names we do not yet know, and perhaps never will. [At Yad Vashem, in their ‘To Each There is a Name’ Project, they have collected roughly 4,000,000 of the 6,000,000 names of the murdered]. It is for these unknown, unremembered souls that I wanted a symbol of remembrance.

Candles and Signs at Gas Chamber following Memorial Ceremony

Closeup of Memorial Signs with Names, and one with the absence of any names

But, after the ceremony, when most people were being herded toward the waiting buses in the far distance, a small contingent—led by an independent Israeli said, “I didn’t come this far to not see the sauna wall!” And with that, he led a small insurrection of descendants who walked in the opposite direction—not to the buses, but other way, to the sauna. I followed them.

There, in front of faces in the photos that I knew so well, I began to tell stories to the descendants who were there. Genya Gutfreund Manela, the Zionist leader who taught her girls about pre-State Israel and about ways to live. Binim Cukierman, the uncle of my dear friend Cvi, the last member of the Cukierman Family, who owned Bedzin’s favorite pastry shop.

A few stories told to a few people. The same thing happened to me when it came time to leave: I could scarcely pull myself away, much like the first time I saw these photos—but, thank goodness, there was a difference.That first time, virtually no one knew about these precious photos, and now people do know. As the former Director of the Auschwitz State Museum once said to me, “Because of the spotlight you have put on these pictures!”

Ann speaking at the Photo Wall at Sauna, discussing Genya Gutfreund Manella

View of the Sauna Wall

As I stood in front of these precious personal photos, for me, it was important that I looked deeply into their eyes. They will never know how deep a part of my life they have become, but I know. And I always will.

Now there was no one left in this corner of Birkenau. By this time, everyone except me was gone, was back on the bus, that is, everyone but Fred Frenkel. Wonderful Fred Frenkel had waited for me—a crucial detail since I had no idea how to get out of Birkenau, nor how to find our group again. Together we walked through a silent Birkenau. As we walked, he told me stories I will not soon forget.

Emilie S. Passow, professor and friend who accompanied me on this trip, noted, ‘Ann, you were not just talking to the descendants, you were ministering to them!” And I might add, because of the scope of these talks and the depth of these connections, in fact, I was not just ministering to them; we were ministering to each other.

Memorial Ceremony at Birkenau, at site of the gas chamber where families died

More stories, more discoveries—and although I thought I was almost finished, meeting these new people and with the new tributaries of the photos probably means more stories, more projects, and more everything. Before I rest, I will try to do whatever I can to keep their memory alive and, not only to remember their deaths, but to honor their lives.

To read a detailed account of the whole journey, written by one of the organizers of the trip, Menachem Rosensaft, from his unique perseptive, please click on the link:

_____

Some (including Menachem in his article) have said that my life’s mission is sharing these photos with the world. Actually that’s only the beginning. Of course I believe that sharing these photos is important, so that others can see faces of people who looked just like them, innocent people whom the Nazis brutalized and murdered. But there is much more that I feel is important. Much, much more.

Letting these people, long since dead, continue to help me teach tolerance, and promote actions that try to make the world a better and more humane place—that is the essence of this work for me.

As my dear friend, Charlie Dibner of Portland, Maine, so succinctly puts it, “The stories you tell are the story of all of us. Your life’s work is to leave the world a little more hopeful.”

I hope I do.

Posted in From Ann | No Comments »