Stories & Photos

Walking Tour at Emory University, Atlanta.

Ann Weiss highlights selected stories in The Last Album, and dedicates the Emory University Photo Exhibition to beloved friend and survivor, Henry Skorr (1921-2010). Video Credit: George Nikos and Randy Fullerton of Emory University

Every picture tells a story. In this case, sadly, many stories are yet to be told. These are but a few.

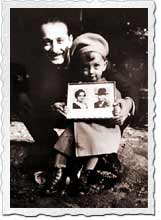

Rozka Monka

Bendin, Poland

“Rozka was very popular with both girls and boys. She had many friends, but her best friend was Fela Rosen. I would often see them giggling and whispering on the couch,” remembers brother Paul. “After all, they were already young ladies! They had many important things to discuss!”

Her siblings recall her kindness, not only to friends and family, but even to people she did not know. When poor people came to their house to beg, Rozka not only gave but gave most generously, sometimes even bringing children into the house to pamper them and to give them a warm bath.

Her heroism during the war is described in the book—and the enormous price it exacted.

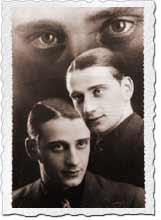

Artur Huppert

Olmutz, Czechoslovakia

Artur Huppet’s inscriptions movingly narrate his delight in being Peterle’s father, and they increasingly document the sense of fear he feels for his child’s safety.

Artur Huppert comes from a comfortable family in Silesia, near the Polish-German border, whose members live in several countries, including Poland and Czechoslovakia. When his parents, Rosinka and Jusekl (Rose and Joseph) were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, they took with them precious photos of their children, this one among them.

In April 1939, Artur inscribed the photo of his six month old son, Peterle:

“My Peterle is laughing at the world. He thinks it all belongs to him. He should be laughing and healthy until 120 years.” He had no indication yet that his child’s world of laughter and security would soon come to an end.

By June 1940, his inscriptions to his parents have become more troubled:

“My child Peterle, 20 months, and I turned 31 years on 9 July 1940. My poor child doesn’t know what a bitter … world he was born into, nor ought he to know that.”

This triple exposure is one of many stylized photos taken of Artur Huppert before he became a father. After he became a father, the baby was the focus of his photos.

David and Renia Kohn

Sosnowiecz, Poland

David and Renia were the children of Bronka Broder of Bendin and Mayer Kohn of Sosnowiecz, a neighboring city in south-central Poland. The Kohn family owned a respected textile store on the main street of Sosnowiecz. Though her family lived in another town, both because of the proximity and because of the love they sahred, both families saw each other very often.

As people who knew her often commented, Bronka was never without a smile or without a book. She worked in the store alongside her husband, Mayer, just as her mother-in-law, Dina Kohn, worked alongside her husband, Nachun. When Mayer married, his parents bought him his own textile store as a present, located further down on the same main street.

The children were well-indulged and well-cared for. Parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, governesses spent much time with the two, and there are many happy photos of the children playing, riding bikes, walking, and being hugged.

When the Nazis came to power, not only were many worlds shattered, but this family in particular suffered a terrible blow very early in the war when the Nazis used the children’s father, Mayer, and grandfather, Nachun, as an example. Five thousand people were forced to watch the punishment being exacted. To this day, some still say, “A day does not go by when I do not remember Nachun Kohn and his son.” In astonishment, to one I asked “Why this event in particular?” The answer: “Because he was such a good man and it was so early in the war. I saw a lot of other terrible things later, but nothing affected me like seeing Nachun Kohn and his son killed. Why? Because I am a religious Jew and I pray several times a day. Every day I say the Shema in the synagogue, I see Nachun Kohn’s face as I say this prayer. His last words were this same prayer, affirming the oneness of the Almighty.”

An Unidentified Baby

Location Unknown

Note the buildings that are important identifiers of location for residents who know this city. Regardless of specific location, the wide-open space in the background where children play and parents walk their baby carriages is seen in many cities.

This baby seems ready to lunge out of the carriage, much like many curious, eager babies. But unlike other babies, this baby’s photo was brought to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where babies had virtually no chance to survive.

Giuliana Tedeschi, a slave laborer at Auschwitz-Birkenau, devastatingly describes the image of empty prams that haunts her long after she and 49 other women were forced to push the prams waiting outside the gas chamber at Birkenau, on Sunday June 25, 1944.

Each face was stamped with a grimace of pain…. The strange procession moved forward: the mothers who had left children behind rested their hands on the push bars, instinctively feeling for the most natural position, promptly lifting the front wheels whenever they came to a bump. They saw gardens, avenues, rosy infants asleep in their carriages under vaporous pink and pale blue covers. The women who had lost children in the crematorium felt a physical longing to have a child at their breast, while seeing nothing but a long plume of smoke that drifted away to infinity….All the empty baby carriages screeched, bounced and angled into each other with the tired and desolate air of persecuted exiles.

Excerpted from Giuliana Tedeschi, There is a Place on Earth: A Woman in Birkenau, translated by Tim Parks (New York: Pantheon, 1992)

In their gripping book, Different Voices: Women and the Holocaust (Paragon, 1993), John K. Roth and Carol Ritttner ask,

“Was it an accident that women in Birkenau were assigned to move the baby carriages, a journey whose yearning and pain, grief and hopelessness, so far exceeded the hour and two miles that it took? It is hard to think so. Far more likely the mentality that created Birkenau would have reasoned precisely: “Who better than women—Jewish especially, mothers even—to move empty baby carriages from a crematorium to safekeeping for the Reich?”

This passage is not included in The Last Album: Eyes from the Ashes of Auschwitz-Birkenau, but I think of it every time I see the photos of the babies in their carriages.